Recently published ACRC research, exploring land and connectivity in African cities, found “land brokers” to be significant players within urban land markets. In Mogadishu, Somalia and Kampala, Uganda in particular, the research found that brokers play a prominent role in influencing land dynamics in the cities – acting as intermediaries in transactions and often directly impacting land prices.

In this episode, ACRC’s land and connectivity domain lead Tom Goodfellow is joined by Abdifatah Tahir from Mogadishu and Eria Serwajja and Muhamed Lunyago from Kampala for a conversation around the role of land brokers in urban land markets in African cities.

They discuss the key role that brokers play in connecting buyers with sellers and facilitating transactions, along with the influence they have over land prices. Highlighting issues that arose in the ACRC research, they also talk about concerns around legitimacy, trust and transparency within brokers’ activities, land value discrepancies, and the need for regulation.

> Read more in ACRC’s land and connectivity domain report

Tom Goodfellow is professor of urban studies and international development at the University of Sheffield and co-led ACRC’s land and connectivity domain research.

Abdifatah Tahir is a research fellow at the University of Sheffield and was formerly a postdoctoral research fellow with ACRC, working on the land and connectivity domain team in Mogadishu.

Eria Serwajja is a lecturer in the department of development studies of Makerere University in Uganda and was part of the ACRC land and connectivity domain team in Kampala.

Muhamed Lunyago is a PhD fellow at the Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR) at Makerere University in Uganda and was part of the ACRC land and connectivity domain team in Kampala.

Transcript

The full podcast transcript is available below.

Read now

Tom Goodfellow Hello, everybody, and welcome to the African Cities podcast. We’re here today to talk about urban land brokers in Africa. And this is some work that’s come out of the land and connectivity domain of the African Cities Research Consortium. I’m Tom Goodfellow, I was one of the leaders of that domain of research in the first phase of the African Cities Research Consortium’s work. And I’m very pleased to be joined today by my colleagues, Abdifatah Tahir, who was working, among other things, on land issues in Mogadishu, and also Eria Serwajja and Muhamed Lunyago, who are both from Kampala, and who led on the work that we were doing on urban land and connectivity in Kampala. And the reason we’re talking about land brokers today is because this is something that came across as being really quite significant in the work, in the research that people did in the cities we were working in, and particularly in Kampala and Mogadishu. So just to give a bit more background, in this domain of work, we were looking at issues around land tenure, land conflicts, how new infrastructure connections affect land values and land conflicts, these kinds of things, exploring the interaction of infrastructure investment and land in African cities. And we were looking at this in Kampala and in Mogadishu, but also in Accra, in Bukavu in the eastern Congo, in Harare, and in Maiduguri in Nigeria. So we have studies on all of these cities. But in Mogadishu and Kampala especially, we found that the role of land brokers was coming through as being really significant in the land markets and land dynamics in those cities. And we had a webinar, which hopefully some of our listeners here might have tuned into, where we talked about all of the cities in our set and a whole range of different findings from our report. And in that webinar, we also got a strong sense from the audience that there was a real interest in this question of brokers and their roles. So we had people joining us from different cities across Africa, and they wanted to know more. There’s also not that much literature, I think, on urban land brokers. A lot of it is focused on different parts of the world and on rural brokers. So we’re here to explore this issue of land brokers more. Let me now introduce, or allow my colleagues to introduce themselves a bit more. I’ll just go round. Do you want to start, Abdi, and just say a little bit about yourself and your background?

Abdifatah Tahir My name’s Abdi. I’m from Somalia, and I was one of the researchers working on the land issues in Somalia in the domain of land and connectivity.

Tom Goodfellow Great. Thank you. Eria?

Eria Serwajja I am from Makerere University. My background is in urban planning, and I also have background in land governance, land tenure administration, and land conflicts that I did at a PhD level. So I also led the land and connectivity domain research in Kampala.

Tom Goodfellow Great. Thank you. And Muhamed?

Muhamed Lunyago I am Muhamed Lunyago. I’m a PhD fellow at the Makerere Institute of Social Research, Makerere University. I was also a researcher in the land and connectivity domain in Kampala City.

Tom Goodfellow Great. Thank you. And just for my own institutional affiliation, which I forgot to mention, I’m based at the University of Sheffield in the School of Geography and Planning. OK. So to kick things off, I want to just ask why land brokers matter? Why is this something that came up as being significant in your cities on the research on urban land and how it works? And, as I say, our stakeholders who came to the webinar also seem to think that they mattered in many other cities. So what difference do you think they make to the city and the city’s development? It would just be good to hear from some of you about that. Eria?

Eria Serwajja I think land brokers are very important in terms of connecting buyers and sellers, particularly in our context, where the land market is less developed. For instance, if a person is looking for land to buy and completely has no connection and has no time, then the brokers often come as a quick fix. So for me, brokers are very important in easing and quickening the transactions, but also connecting those that are willing to buy and willing to sell. So without them, like it was in the 1980s and 70s, it was often very difficult for somebody who even had the money to buy to find an authentic seller of the land. So in that context, for me, the land brokers are very important and have become a crucial part in terms of land transactions. Although they operate informally, in my view, many of these transactions often find their way into the formal system. So their informality is somewhat becoming a little bit formal. So for me, from the context of the work we’ve done in Kampala, that is the value of land brokers.

Tom Goodfellow OK, that’s fascinating. Thinking about cities that are growing as fast as Kampala – and some of that growth is internal, but some of it’s from migration – this sense that it eases people’s entry into the city, right, being able to find a plot of land for people who are unfamiliar with the local scene. And I think we should come back to that issue of them becoming more formal as well. But maybe we can hear a little bit more on Kampala from Muhamed before handing over to hear about Mogadishu. Muhamed.

Muhamed Lunyago Sure. Well, I think land brokers are becoming important also because the people themselves, especially those that want to buy land, find it a little bit convenient to go through them, given the time it would take them to look for land anywhere. Kampala is quite a huge city and not everyone in the city knows all the places and which places have which kind of amenities and infrastructures. And yet the brokers have most of this information. And if they did search for land by themselves, they would actually take a lot of time and then a lot of money, it would cost them quite a lot. So going through a broker who actually has more of this information, because one of the roles they play is to gather this information and be able to pass it on to the prospective land buyers is what they do, and then becomes a little bit convenient.

Eria Serwajja I think also, Tom, the issue of brokers having multiple options, you as a buyer of the land, you could actually be looking in one direction, but the brokers often have this array of options and they will take you to multiple pieces of land where you’d actually think that some of that could be much better than you had imagined before. So for me, they offer, apart from shortening of time, those options that come to the table are very crucial for the buyer.

Tom Goodfellow OK, so does what you’ve heard there, Abdi, speak to the situation in Mogadishu in terms of their role and how they work? Or would you describe anything differently in the context of Mogadishu?

Abdifatah Tahir I think Muhamed and Eria’s discussion regarding Kampala very much relates to Mogadishu as well. But in addition to what they’ve already said about Kampala, in Mogadishu, obviously there are, because of the conditions of fragility, there are overlapping claims on land, and property ownership is not very clear. So the work of the brokers becomes so important in that regard, in the sense that it becomes like an issue of security. For instance, if you want to buy land in Mogadishu and you don’t know about the clarity on the ownership and sometimes you don’t even trust the papers and all of that, they become an extra layer of security in finding out the right land, who it belongs to and all of this. So their work then comes across as a very important component of the land market in Mogadishu.

Tom Goodfellow OK, so in some senses, when in any situation where you buy and sell land or property, these agents come into play. And, here in the UK, obviously we talk about estate agents, who are heavily formalised and there’s a certain degree of transparency in how they work. And of course, there are formal estate agents, certainly in Kampala and I imagine to some extent in Mogadishu. But how are brokers different? So I’m interested in the language that’s being used as well. Maybe before we go any further, what words are used locally? Because when we were talking with our other colleagues in Nigeria and other contexts, we found, I think, when we were talking about brokers that people meant different things. So some people were actually thinking more of perhaps developers who might buy land, subdivide it, do a bit of work and sell it on, rather than just connecting buyer and seller. And of course, you have sometimes high-level aggregators of land parcels and they all might have different words that go with them. So it would be interesting to know, in your context, what is the word people are using? What does it translate as in English, do you think?

Abdifatah Tahir In Mogadishu, they use the word “dilal”, which more or less means like intermediaries. It is just somebody who arranges the transaction between you and the seller of the land. And it is also about having accurate information about the land they are selling. So I think this word dates back… the brokerage system when it comes to land, it’s not a very old thing. It’s a new phenomenon. It only started in the 80s, due to the urbanisation trade that has gone quite high at the time because of many people going abroad, especially in the Middle East, where they had to work and were remitting significant amounts of money to build houses for themselves. But before that, the word dilal, which is like the intermediaries, it was often used for the livestock market, where traders used to arrange the sale between the rural folks who own livestock and the urban folks who want to buy from them and export it to the Middle East. So the intermediaries between that particular trade. Then it was in the 80s – it only gained momentum in the 80s – that it became also applied to other markets, like other forms of trade, including goods import from outside and people who do the intermediaries, as well as the land market. So dilal is not something unique to the land market. It also applies to all sorts of intermediaries, including goods, exchanges, as well as the livestock.

Tom Goodfellow That’s really interesting to hear that background of how brokerage has kind of moved from other places, like into land relatively recently. How would you tell that story in Kampala, Eria?

Eria Serwajja Yeah, for Kampala, the word is “kayungirizi”, meaning the connector, the person who connects one person to the other. I mean, the person is connecting the buyer to the seller. But other terms, like “dealer” have also come in, a person who is into a deal, which is you’re trying to do something for quick money. Quick money means there is a buyer, a person who has the land to sell. So you’re looking for a buyer and you’re getting some little money off it. So that’s your intention here. But there has also been a transition, as I’ve heard from Somalia. There has been a transition from people who have been kayungirizi or the connectors or the dealers into real estate. Many of the kayungirizi or the dealers come together to start buying portions of land, which they cut into small pieces, apportion into small pieces, 50 by 100 or 50 by 50 or 100 by 50 and they are for sale. So this transition is now seen in Kampala, where brokers have now transitioned into some sort of real estate dealers in a way. So, again, but they don’t often abandon their dealing role or their connecting role. They continue to do it, but they now become a little bit bigger with some bit of money and therefore can become real estate dealers.

Tom Goodfellow So this picks up on what you were saying earlier, I think, about how they’re becoming more formal. And there are obviously real estate agents who are quite high end and have a formal office and maybe have registered their business formally. And you can go there and look at pictures and they’re online. Is there a hard line between an estate agent who is formal in that way and these brokers, or is it more fluid, are they, one can become the other? I’m just wondering about the relationship between the formal and informal there.

Eria Serwajja Within our country, I think there’s a thin line between the formal and informal. But I want to take you back a little bit to how this land brokerage started. In Uganda, there was one gentleman who was called Kasule and that particular time, the term was “Kasule” property agent’. So one individual comes up with the idea to start connecting buyers to sellers and he was the only one in town. And his downfall was that he expanded so quickly to almost different parts of the country. But my thinking also is that the politicians became a little more threatened because he became so powerful within Kampala. So he had land and connections across the country. So in that line – and land is a political issue in our country, it embodies all those socioeconomic and cultural aspects – so in a way, he collapsed terribly. But that is how real estate and brokerage started in the country. He was actually, the land broker did not exist in fact, his name was Kasule then, that everybody who mentioned his personal name would ideally point to land brokerage or a person who is connecting buyer to the sellers. But his company collapsed. And of course, he became indented, he was pronounced bankrupt. And up to now, he lives a very silent life in Kampala. But he had transitioned the country from this informal process that people do not know that there is anything like land brokerage. And everybody now started picking up land dealer, land broker. And now the entire country, you find every other small town and village has a land broker, whatever you want, whether in Kampala or out of Kampala. Every village, whether they are LCs, have also become land brokers. So there’s a thin line between the formal and informal. In fact, those that are informal often start to formalise and they have offices and they have bank accounts and that’s how the process goes. But when they become bankrupt, they now fall back into the informal system. So there’s a fluid kind of line and thin line between formal and informal.

Tom Goodfellow OK, so this is interesting. This gets me as well onto this issue of legitimacy and trust, because it’s clear that these actors have gone from being non-existent actually quite recently, over a few decades, to being really key players in the land market. And clearly a lot of trust has to be put in them, in terms of the information that they hold and people considering it to be reliable or valid. But there are also maybe different categories and it’s interesting to hear there are different words which perhaps have different degrees of legitimacy. So I wondered if you could just say a bit more about, are these actors in general people who are trusted? Are they seen as a positive actor in the city that people really need? Or is there some sense that there are distinct categories? There are the real ones, the legitimate ones and the illegitimate ones, regardless of formal or informal categories.

Eria Serwajja It was largely practised previously by unemployed young men and young women. Of course, very few women – it’s just now that they are entering into the system – but unemployed, less educated, that category of persons who do not seem to have hope, if I could say that. So by their very nature, it means that there’s less trust in this category of persons. It means that the information they hold sometimes is very untrue, that you can’t trust such a person. So the trust initially wasn’t there. It’s now that when you start to formalise, you start to give people hope that I am the legitimate person, I have an address, I have an office. And those particular issues become very important, in terms of sieving out who is formal and who is informal. So formalisation means there is an office, they have an address, you have legitimate phone numbers and now they advertise, which wasn’t there before.

Tom Goodfellow I think there’s a few things that I want to pick up. But come in, Muhamed, if you’ve got something to add there.

Muhamed Lunyago Yeah, I think also on the question of trust, people as of now seem to appear like they don’t have a choice than to deal with the brokers, whether they trust them or they don’t trust them. So they just rely on the fact that, well, we don’t have a choice. We cannot do this on our own. And you could become a little bit more vulnerable to risks of theft and robbery in the land transaction than you would when you’re dealing alone. So they don’t trust them that much. But it’s like they don’t have much choices, you know. Also, given the fact that even some of the land sellers actually want to hide some of their transactions from maybe their close family members and associates and stuff like that, that it becomes quite difficult for them to deal directly with some land buyers and then they have to go through brokers. And it’s quite hard to know who is selling which kind of land if the land seller himself is not putting up a poster or telling people that I’m selling. The first point of contact for them is to go to a broker and people just find it a bit convenient to go to them, not because there is a lot of trust in what they do, but because the options they have without the brokers are quite limited.

Tom Goodfellow Yeah, that’s really interesting as well, because it’s like some people obviously want the whole thing to be quite secret. They want to use a broker because they’re concealing something they’re doing. They don’t want the sale to be visible. So that issue of the secrecy of brokers is kind of baked into what they do. And obviously for other people, that can be risky because you don’t know if they’re actually ripping you off in all kinds of ways. But yeah, there is a tension there between wanting it to be secretive and wanting to have that transparency. I’d just be interested to hear from you, Abdi, about those issues around legitimacy, trust, concealment in the case of Mogadishu.

Abdifatah Tahir Yeah, in Mogadishu actually, for maybe the purpose of determining the price, initially you may even conceal the information, the correct information regarding how much the land was intended to be sold. But at later stages, it becomes evident because you have to meet who the owner is. And in the case of Mogadishu, the transaction takes place not between the broker and the person who is buying the land. It is rather between the seller and the buyer. So the broker’s role is the facilitator of the transaction between these two parties. And for that reason, the concealment of information is as much as it regards only making sure that you don’t directly make a contact with the person who is selling the land. And when the transaction is agreed upon, then the two parties are brought together and it is final. So concealment goes as far as that. Regarding the trust, I think since there is no money that will be given to the brokers directly in the beginning, there is not much of an issue regarding whether a broker is trusted with the money. But the trust issue comes into the picture as regards the price, because if the broker hikes the price, it means also more commission for him, especially if the commission is coming in the form of a percentage of the total amount for which the land is to be sold. So in that case, there is a bit of mistrust in that aspect. But more generally, people trust them, mainly because of the fact that it’s very difficult for you, as the other two speakers said, to find a land for yourself, unless you have these intermediates, who find it for you.

Eria Serwajja Yeah. Tom, you’re talking about trust, but we’ve also seen in Kampala that brokers do not trust landowners. So this also trust is two ways. In Kampala city, brokers have gone to the extent of signing agreements with the land sellers, those that are putting up land for sale and agreeing on the price. And this price is even being put in the agreement, although it’s illegal, it’s not within the law that a broker can make an agreement with you, the seller, because they are not the actual buyers anyway. But this is what is happening. So this trust is also two-way for Kampala, that the brokers also don’t trust. In fact, there is a word in Kampala that they use when they are referring to you as a seller, who makes a U-turn after realising that the broker is getting a lot of money. They will ask you, if I may directly translate, that’ I hope your heart will not bulge, will not become big’ – “Tojja kuzimba mutima”. It means that when you see that the broker is getting a huge percentage because of the amount that is going to the broker, then you make a U-turn as the seller, because you think they have not done anything, they are getting free money, and therefore in their own terminology, they will say that the seller gets a bulging heart. It means that you become envious that they are getting free money. And that’s why many of them are starting to have this argument, to say, I hope, Tom, you will not be able to change your mind when you find a buyer. So can we reach an agreement if we think you’re going to change your mind? And these agreements are starting to emerge, as we’ve seen in Kampala.

Tom Goodfellow But it seems the issue is also the brokers can not only take their 10 % fee, but they can also take sometimes the difference between what the seller says they want, and then what the buyer actually pays. But I think…

Abdifatah Tahir That’s a bit of a difference in Mogadishu, because the transfer of money will be taking place between the seller and the buyer. So it is not like between the seller, the broker and the buyer. This is not in that order. So that is why, other than what is stated, there is no hidden cost.

Tom Goodfellow You can’t conceal.

Abdifatah Tahir You can’t conceal.

Tom Goodfellow It seems like in Kampala there is sometimes some concealment going on between what the buyer is paying and what the seller knows. Is that right, Eria?

Eria Serwajja Yeah, sometimes that happens for Kampala. But the thing is that there has to be an agreement written. The issue is that the broker will negotiate with the buyer separately, they agree on a price, and then come to the seller to say, this is what comes to you. In the end, all this has to be factored in the agreement. But that must also come to the knowledge of the seller. And at that point, when the transaction is going on, because they either go to the bank, normally these ones go to the bank because it’s huge monies, and often transfers are done in the bank. Sometimes it’s cash. Of course, it’s risky, but it happens, particularly for money that is either corruption money or money from these illegal deals. So that often happens. But the thing is, at that point, then you have that mistrust, boils up to a certain point to say, I am not giving away my land because you’re taking much. But we’ve seen, and I’ve spoken to people in Kampala, people who have been attacked by brokers after selling the land where you had a first batch of brokers give you the actual price. For instance, if my land is 15 million and the brokers find a buyer who is 20 and you make a U-turn and you say I’m not selling any more, when they realise that you have sold the land with another batch of brokers at 20 million, they will say, hey, we came here, you wasted our time. And I’ve seen one particular example and spoken to one person who has been attacked in a way.

Tom Goodfellow By a broker? Yeah, yeah. So the technicalities of paying and selling make a difference to how important trust is, to who’s able to extract more money. I just want to turn to the kind of implications of this for people concerned with broader urban development and equality and inclusion issues. Has this really pushed up the price of land in a way that might exclude poorer people from access to land? Because I guess you can argue before there were brokers, people might be able to charge whatever they wanted for their land because it was harder for buyers to find a plot of land. But at the same time, brokers mean that there are many more buyers who might be able to access one plot. And so that could push up the demand and push up the price. How do you think the role of brokers is affecting the prices of land in your cities? Is it having a significant impact?

Eria Serwajja Yeah, Tom, for our case in Kampala, there came this category of brokers called special buyers. That was what they called special buyers, the category of high-end politicians, those that work within… And another term that came up is “Kutikkula” meaning offloading – those who have offloaded from the Treasury – and that was the phrase that was used. If someone has offloaded money, has stolen money from the Treasury, that person is willing to pay any price. So one of the brokers that we engaged in Kampala, indicated how a particular land buyer from one of the neighbouring countries told him that “I want to buy off my neighbour. Please ask him how much he wants for his land, including the house where he lives”. And the person said, “No, I am not selling”, and sent him again to say, “please go and ask him. I’m giving him a blank cheque. Let him write how much he wants for his land”. And the person, I think, asked for money. But the broker knew exactly how much this person had reserved to buy the neighbour’s plot, to buy him off at whatever cost. So when this person wrote the amount of the money on the blank cheque, the broker just laughed it off. In any case, the broker became much more rich because he made a huge amount out of that deal. But indeed, the buyer, who was a foreign national, bought off the neighbour, to expand his land, was not willing to relocate and go out of town, so this land brokerage is also going to drive people to landlessness. And we’ve started to see this happen. The, I forget the term, but the issue is you would not be selling the land, but the amount of money that is being given to you may make you think overnight. And the following morning you make a decision to sell off your land, sell off your house and any other property because of the obscene amount of money that is being put on the table through this brokerage, money laundering schemes around Kampala. You’ve heard about the billions of money in Kisenyi that made headlines in the newspapers and the newspaper indicated that that is the most expensive land on the African continent, just one acre, better than Cape Town or Cairo. So at the end of the day, these particular processes are going to push urban landowners, but who are the urban poor, into landlessness, because this is what it is at the moment.

Tom Goodfellow So if I understood right, you’re suggesting that there are people, and maybe this would apply to people who farm land on the fringe of the city and so on, who would make themselves landless because they can see all this speculation and money coming in, often from money laundering, that they would, even if they had no plan to sell their land, they would give up their land and potentially their livelihood for some quick money. And this is actually causing long -term problems in the city.

Eria Serwajja Absolutely.

Tom Goodfellow It’s very worrying. I’m not sure if anyone else has any thoughts on that question of inclusion and landlessness. Muhamed?

Muhamed Lunyago Yeah. You know, in the case of Kampala, so the highest price paid for a piece of land in an area sets the standard for the remaining pieces of land surrounding it. When someone comes and buys a plot of land in an area, say maybe 200 million shillings, and when initially the cost of that particular land was 50 million shillings, most of the people would be asking for money in the range of 200 million shillings, because that alone sets the standard for how much that land can cost around there, because they’ve seen it happen. And usually some of the people that are able to pull up these amounts of money to buy a plot of land want to protect themselves from not having these many poor people surrounding them. So they will try as much as possible to come and buy off most of the neighbours and also influence others in their circles to come and buy such pieces of land. So in the end, you realise that first the land is becoming too expensive for the poor and sometimes also the middle class, but also they are forced off the land, either by the amount of money that is paid, like Eria is saying, or you are forced off completely, sometimes violently, to leave the land because of the protection that these people need for themselves. Yeah.

Tom Goodfellow And the brokers themselves, Abdi, did you want to come in on some thoughts on Mogadishu there?

Abdifatah Tahir Yeah, in Mogadishu, brokers as well drive, as already has been said, speculation in the city. In the sense that, as Muhamed was saying, it so happens that the asking price of a particular plot of land in a given area determines what comes after that. So it’s not based on a rationale or real assessment of what the real land value of that plot is. It is based on what the next plot has been sold for. So that is very common. And it creates a condition in which many people, not necessarily are a fool, but rather on the fact that the price they would be getting for a piece of land is a lot higher than the real value of it. They sell their land and maybe later on, then again, struggle to find similarly convenient land for them. So it complicates things like commuting to work and all that, because they may sell their appropriately located land, which had maybe better access to all the amenities they need, or maybe the work facilities and all, or maybe the opportunities of work available for the poor people in that sort of land. So it creates a lot of layered problems for the poor people in the city. And in the case of Mogadishu, it particularly attracts a lot of money from the diaspora, which invests in areas they think maybe would have a very good land value, in case they decide to resell. And even that, Mogadishu was experiencing a new class of middle class elite, mainly because of the aid money and because of the booming trade in the city. There’s a new class of economic elites who tend to buy land as a form of investment for the future, predicated on the fact that they think it would sell for a much higher price for them in the future. So these are the things which are negatively affecting the poor people in the city.

Eria Serwajja Yeah, so one issue that I think we see what is happening in Mogadishu being similar to what happens in Kampala. But though the challenge, I think from my end, is governments do not seem to have clear ideas on land values in different areas. That when you have a special buyer like Uganda National Roads Authority, which would be, for instance, compensating for expansion of the road and compensating those people that are very close to the infrastructure, then that sets the price. I mean, you have a government institution with, say, World Bank funding, which is setting the price for the localities within. And that often becomes a challenge that we have also, in our case, where people invite to say, my property should also be taken, because they know when Uganda National Roads Authority, you know, is compensating, it does not compensate like a normal person like Eria or Abdi or Mehdi. So at the end of the day, people keep inviting, “please let also my property and my land be affected”, because they know this is the time to make money. So the lack of clear land values for particular areas set by the state, but of course within a neoliberal economy, then also becomes very difficult. How does the state intervene when it’s open market? So that’s the kind of dynamic, I think, that we are in.

Tom Goodfellow We’ll come back in a minute to the question of state regulation, I think, as we perhaps wrap up. But I mean, it’s obviously normal for land values to be determined by other values in the area and not by the state. Right? I mean, so the way in which land values are assessed is obviously through market processes that are connected to perceived value in certain areas. But I’m wondering about the role of brokers within this. Right? Because in the academic literature on land brokers, there’s quite a lot about India and a lot of it’s quite rural, as I said. But there’s this debate, are they just linking people in a market, lubricating, connecting or do they have some kind of agency? Are they actually doing various things, the tricks of the trade that push those values up? Do you see what I mean? Like the brokers themselves. And I just wondered how you see them in that way. Are they actually making the market, shaping the market in some way, rather than just these connectors? It seems to me from some of the things you said that they have some significant agency here, right? In terms of the things they do to build. Yeah.

Eria Serwajja Yeah, they’ve made a transition, of course, as indicated earlier from how land brokerage started. I mean, even the terminology “brokerage” now has become mainstream, but initially it wasn’t there. So there has been a transition, with many of them becoming a little bit formal, establishing offices, we have these contacts. Now the debate within our country is to have them more formalised. There is the Real Estate Bill, which is before parliament. And any time when it gets to the end of the conveyor belt, then it will be mandatory for a broker to be registered with an address and within an association so that the state has this hand within the brokerage dynamics that they can be sanctioned. You can be thrown out and new ones come through. So they are getting formalised within the mainstream and institutional systems and processes of the government. So in a way, this is what is happening within our end. And brokers, by the way, are also rushing very fast to form associations. You have area association, Real Estate in Uganda, for instance. You have all these small but emerging associations which are going to be finally within the mainstream government establishment.

Tom Goodfellow OK. Yeah, I’d like to come back in a minute to what that means. If they want to be formalised and everybody is on the same page about this, then maybe that’s quite a positive thing going forward. And perhaps this period of a slightly Wild West brokerage with a lot of violence and conflict and extraction – things might be moving in a more positive direction, perhaps. But before we perhaps reflect on that question, I wanted to pick up on a few things you said around women and also around the digital revolution in communications. I’m not sure whether those things are connected. But, because you said that more women are now able to enter this profession as brokers than in the past, which is interesting, so I’m wondering how common that is and if it’s been in part facilitated by a lot of things becoming digital. And more generally, it would just be really interesting to hear about the digital mediation or the digitisation of brokerage and what effect that might be having on the land market, on who gets to access land.

Abdifatah Tahir In the Mogadishu case, I guess, the brokerage system is not so much technologically mediated, in the sense that you won’t see a lot of brokers. There are a few agencies, of course, in Mogadishu which act like normal – or what could I say? Normal might not be the right word – but the usual real estate agencies that you see in other countries. But when it comes to the brokers – the land brokers, we’re talking about – they don’t use the social media so much in the case of Mogadishu. I don’t know the reasons for that, but it’s not a platform that they commonly use. The other thing regarding the gender issues of land brokerage in Mogadishu, there is not, again, many female brokers in Mogadishu. They tend to be mostly under-50 male, not necessarily all young, like it comes across in other cities. The age – in Mogadishu brokers tend to be not age -specific, like all young, very young – it’s between anywhere from 20 to 50, or even more.

Tom Goodfellow So I think it’s interesting, because so much is digitally mediated in Somalia, that brokerage doesn’t seem to have gone online in the same way. My sense was in Kampala, that’s happening a bit more. But maybe on the gender issue, it’s that this enables women to sell and buy land more, rather than to become brokers themselves, or perhaps they’re doing both. Some reflections from Kampala would be interesting there.

Muhamed Lunyago Yeah, you know, women joining the land market as brokers is two-way. First, given the difficulties many of them have been facing in buying land or selling land and being targets of people who engage in land fraud and all sorts of stuff, so many of them, we had an interview with one woman who heads an organisation, a company called Fabulous Homes that buys land, that collects a number of women, they collect money across the year, then later they buy land and then share the acquired land with those different people and sometimes go ahead to build on that kind of land. And many of them have joined because of such kind of difficulties to selling and buying. Others have joined because of the other challenge, like unemployment. Many women are unemployed and then they are in the city, they have to survive. And they see this as the window through which they can come and then find a living. You know, because you can wake up one morning, design a poster, put your phone number and your name and put “land broker” and then put it there. And if you have nothing to do and it will cost you something like 2000 Ugandan shillings, which is less than a dollar and you have it, you easily join the market. So it’s two-way. Also, I think the internet has tried to help a bit because initially it would be hard for a number of women to have access to information on land which is available for sale in different places and different locations. Given that a majority or maybe a big number of women are engaged so much in doing domestic work or even those that are involved in informal kind of employment or even formal, after leaving work, you’re going home, you have to go and do the domestic work, some kind of social reproduction work that is waiting for you there. So you may not have enough time to go and socialise and interact with people that may have such kind of information. But with social media, if you are at your workplace, you could get up the internet and then you could find a plot of land that is being sold in a place that you like and you could easily have access.

Tom Goodfellow There have been so many interesting issues raised here. I think we’re running out of time. I would just, as we wrap up, in this context, this picture you painted in both cities really of a quite rapidly changing situation, where brokers have become really important, they’re starting at least in Kampala to perhaps become more formalised. We’re seeing the role of digital transformation in that context as well. There are varying levels of trust, there are different categories, but maybe there’s a sense of organisation and movement towards formalisation. So I just wondered what you think, to wrap up, the state should be doing. If you had some advice to make sure that brokerage worked as well as possible for the wider city population, what might that be? Any final reflections there really on what the relationship between brokers and the state and forms of regulation might look like going forward?

Eria Serwajja From our work, for ACRC in particular, the project that we sort of tried to propose moving forward, one way would be to have the brokers, you know, have a very strong association. It helps them, one, to also put their demands across to the state if they are within a strong association. Number two is that the trust goes up when you have this strong association. It means that the members that do anything contrary, including fraud and stuff like that, can be sanctioned or even expelled from the association, meaning that trust goes up within the local communities and they will be in business. Number three is that the issue with the brokers in our country has often been around many of them getting into acts of fraud, not being known by the state. So through the real estate bill being formally recognised, it gives them special status and recognition and they can sit on the table with this government and say, this is the direction where things should go. And therefore, you have a voice that you can use to advocate for whatever interests that you have.

Tom Goodfellow It sounds like things are moving in a positive direction. I guess the issue is really more around regulating the activities of those special buyers and on wider issues around illicit finance and money laundering and how that inflates the land market, rather than the brokers themselves. I mean, there are ways in which maybe the brokers can exacerbate some of the problems around inflated land prices and so on. But the fundamental problem lies somewhere else, I guess, and brokers themselves just want to be able to have a degree of transparency and formalisation, it sounds like.

Abdifatah Tahir Yeah, I think formalisation would be good, but in a limited sense, especially as it regards maybe providing a framework, a legislative framework within which maybe brokers can register themselves and minimise the sort of, somebody just coming, waking up in the morning, as Muhamed was saying, just somebody waking up in the morning and becoming a broker the next day without having maybe sufficient knowledge about how the market works and all of that. So I think in that regard, it would be nice to have some sort of regulation. But again, on the same note, I would probably be a bit concerned about the state having too much role in it, in the sense that the minute you try to regulate things like corruption through putting in place legislation that look at how brokers are making an investment whose source is not clear, that minute, then you create a whole sort of other problems, like a capital flight from the country where people then invest their money, their illicitly gained money in other countries because they know you will find out through the brokers, the regulations imposed on the brokers and all of that. So it creates another sort of a problem which negatively impacts, not only the market, but the country, but the employability of people, all of these sorts of problems. I would be very careful about very strict formal regulations.

Tom Goodfellow And those are obviously really important trade-offs in a country like Somalia.

Abdifatah Tahir Yeah, maybe one more thing. Self -regulation as well would be very important in conditions of fragility like Somalia, where they state if you give them all the teeth they need, industries like this might be negatively affected. So self -regulation, again, is another thing which in combination with formal regulation would work well for contexts like Somalia.

Tom Goodfellow It sounds like a degree of that self-regulation is starting to happen in Kampala. Muhamed, I’ll give you the final word.

Muhamed Lunyago Well, yeah, I think I will not differ so much. I think, like Abdi and Eria have been saying, the state providing a framework within which brokers can be organised, not necessarily talking about regulation in itself, but also organisation. So if they are organised, perhaps most especially by themselves as brokers, maybe they have a union or an association and stuff like that, they could easily try to deal with the many problems that paint a bad image of themselves. Because their work is important, but the other things that go through like fraud and others make their work quite problematic. But also, regulation of brokers in isolation may not solve the problem because the problem is way bigger than brokerage itself. So alongside trying to provide a framework to organise and regulate brokers, we have to deal with the other problems, like how people are getting the huge sums of money. It may not necessarily be determining the price of a particular piece of land, but trying to find out who owns this very expensive plot of land. And what’s their source of income? What does this mean to these kinds of people? So the whole idea of commodifying land is one of the problems that we have. If we could think of land not as a commodity that should hold our money and then think otherwise, the other values that come with land, it could be something very important.

Tom Goodfellow Excellent. I think that’s a really good note to end on. Thank you, Muhamed. Thank you, Abdi. Thank you, Eria, so much. I’ve really enjoyed this conversation. For listeners who are interested in these issues, please do check out our crosscutting report on land and connectivity in six cities, which is on the African Cities Research Consortium website, and also the individual city reports as well, which might have more information on this. So thanks for joining us and goodbye.

Outro You have been listening to the African Cities podcast. Remember to subscribe for more urban development insights and interviews from the African Cities Research Consortium.

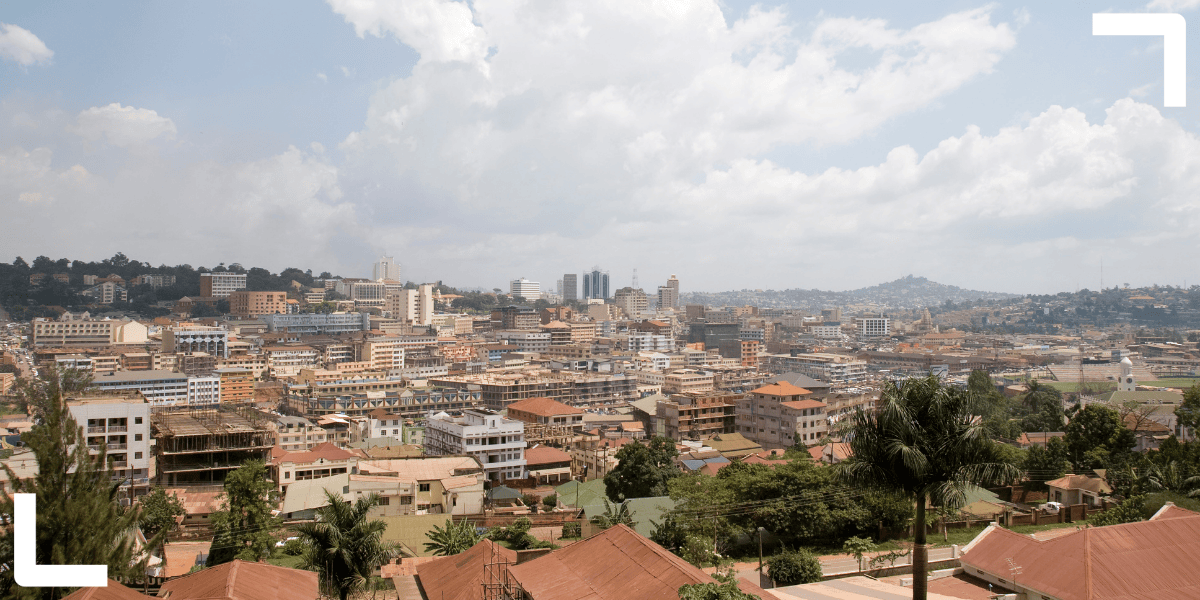

Header photo credit: Frank van den Bergh / Getty Images (via Canva Pro). Aerial view of Kampala, Uganda.

Note: This article presents the views of the author featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.