By Michael Danquah and Kunal Sen

Structural transformation involves the movement of workers from low-productivity sectors to high-productivity sectors. It has historically been associated with a shift from agrarian economies to more industrial economies based around urban areas, as seen in many Western nations as well as the Southeast Asian giants. For these economies, it is thought to have been crucial to economic growth and poverty reduction, by creating jobs and improving labour productivity.

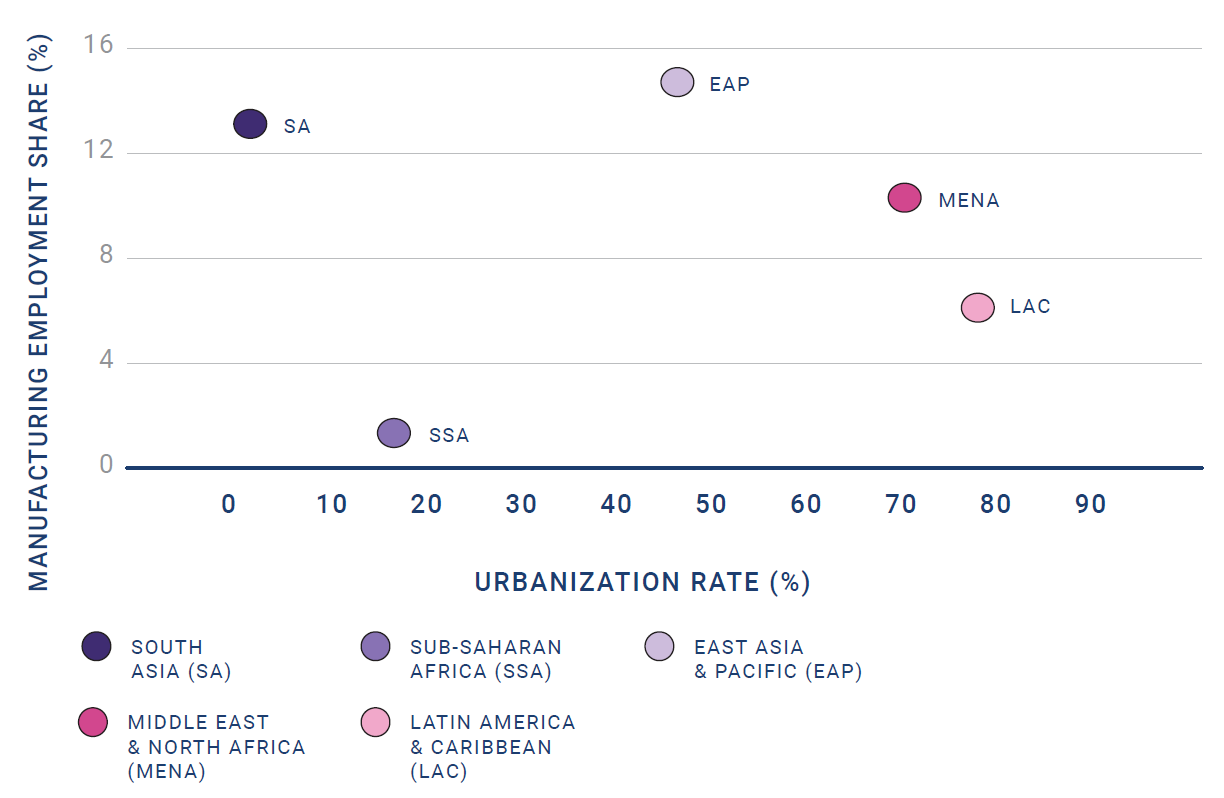

In many African countries, however, the prospect of a thriving manufacturing industry seems difficult to realise. Urbanisation has taken place without structural transformation with the share of employment in manufacturing in sub-Saharan Africa far below South Asia, even though South Asia has a lower urbanisation rate than sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 1). Further, African cities’ economic sectors are dominated by low-productivity, informal enterprises, most of which are found in the services sector – specifically wholesale and retail trade, while a few enterprises are engaged in informal manufacturing. Large segments of Africa’s urban population work in the low-paid, informal wage economy, often self-employed.

Figure 1: Share of employment in manufacturing vs urbanisation rate (2015), by region

Sub-Saharan Africa’s urbanisation rate, or the share of the population that lives in urban areas, is low but growing rapidly. What is unique about sub-Saharan Africa’s urbanisation rate (compared to other regions), is that the region’s urban population is expanding despite a notably smaller share of workers employed in manufacturing.

Note: Urbanisation rate is calculated by dividing the urban population by the total population.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the GGDC/UNU-WIDER’s Economic Transformation Database and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI).

A street food seller in Accra, Ghana. Photo credit: Dave Primov / iStock

Disentangling the connections between Africa’s cities and the slow pace of structural change will be essential for creating growth and reducing poverty, as structural transformation has the potential to foster economic diversification and inclusive growth. For effective policymaking, it is important to understand the drivers of structural transformation at the city level. It is also crucial to understand what alternative patterns of structural transformation – that is, leapfrog development (economic transition from agriculture to services, jumping the manufacturing stage) – might mean for the sustainable growth of African cities.

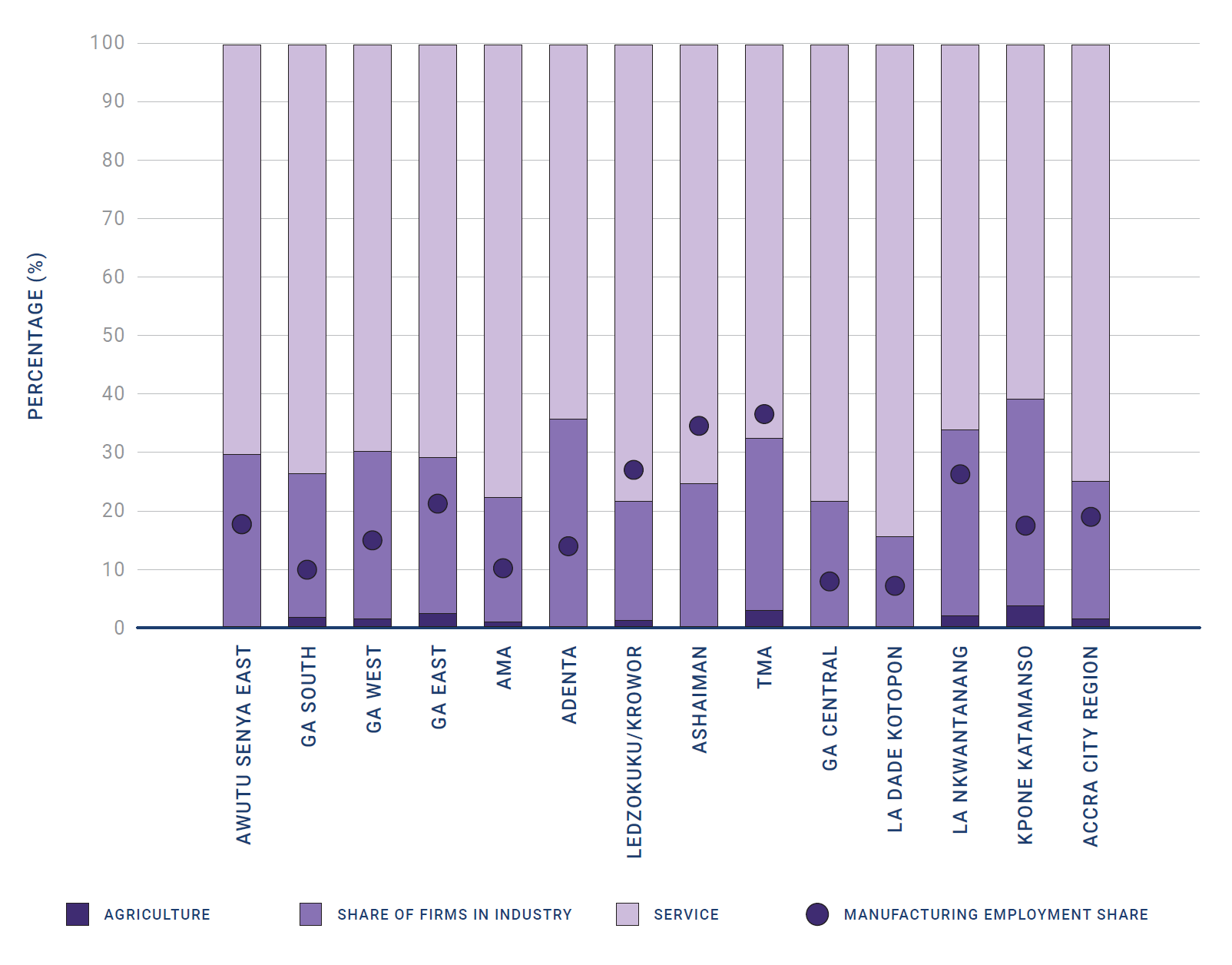

For example, the economic landscape in Greater Accra, the capital of Ghana, provides a picture of this experience. At the sub-city level in Accra city region, economic activities are dominated by the services sector largely made up of informal enterprises. The share of manufacturing establishments and employment are very low compared to services (Figure 2). Productivity at the city region is generally low, but it is not homogenous across the different areas of the city. This leapfrog development (from agriculture to services) has not resulted in the creation of productive jobs in the city.

Figure 2: Shares of establishments in each sector and shares of manufacturing employment across districts in Accra city region

Most Ghanaian firms are engaged in the services sector, while only very few are involved in agriculture. The share of firms in industry varies from 15 percent to 36 percent, depending on the district. In Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA), only about one in ten workers is employed in manufacturing.

Moreover, the organisational type (private limited) and formality and institutional performance of city governments seem to correlate with low productivity of enterprises.[1] Some of the major constraints to enhancing productivity and economic transformation in the city include access to long-term finance, high cost of production especially for energy, land, transportation, and space for business operations, higher costs for public services due to bureaucratic tendencies by city officials, and excessive influence of political leadership and interference at the sub-city level.[2] City governments would need greater capacities, resources, and support to improve the performance and productivity of enterprises – particularly the establishment of new manufacturing enterprises in the city.

Further, there is room to transfer some of their services to the private sector, work together with relevant institutions to carry out appropriate land reforms, and seek investments in critical infrastructure that would help the growth of high-productivity enterprises. Given the rapid increase in the size of African cities, as more workers move to urban areas from rural areas in search for jobs, urbanisation must be accompanied by structural transformation in Africa. Consequently, policies that foster productivity growth among formal and informal enterprises, as well as deliver productive jobs for Africa’s urban workforce will be critical to the success of the continent in economic development in the years ahead.

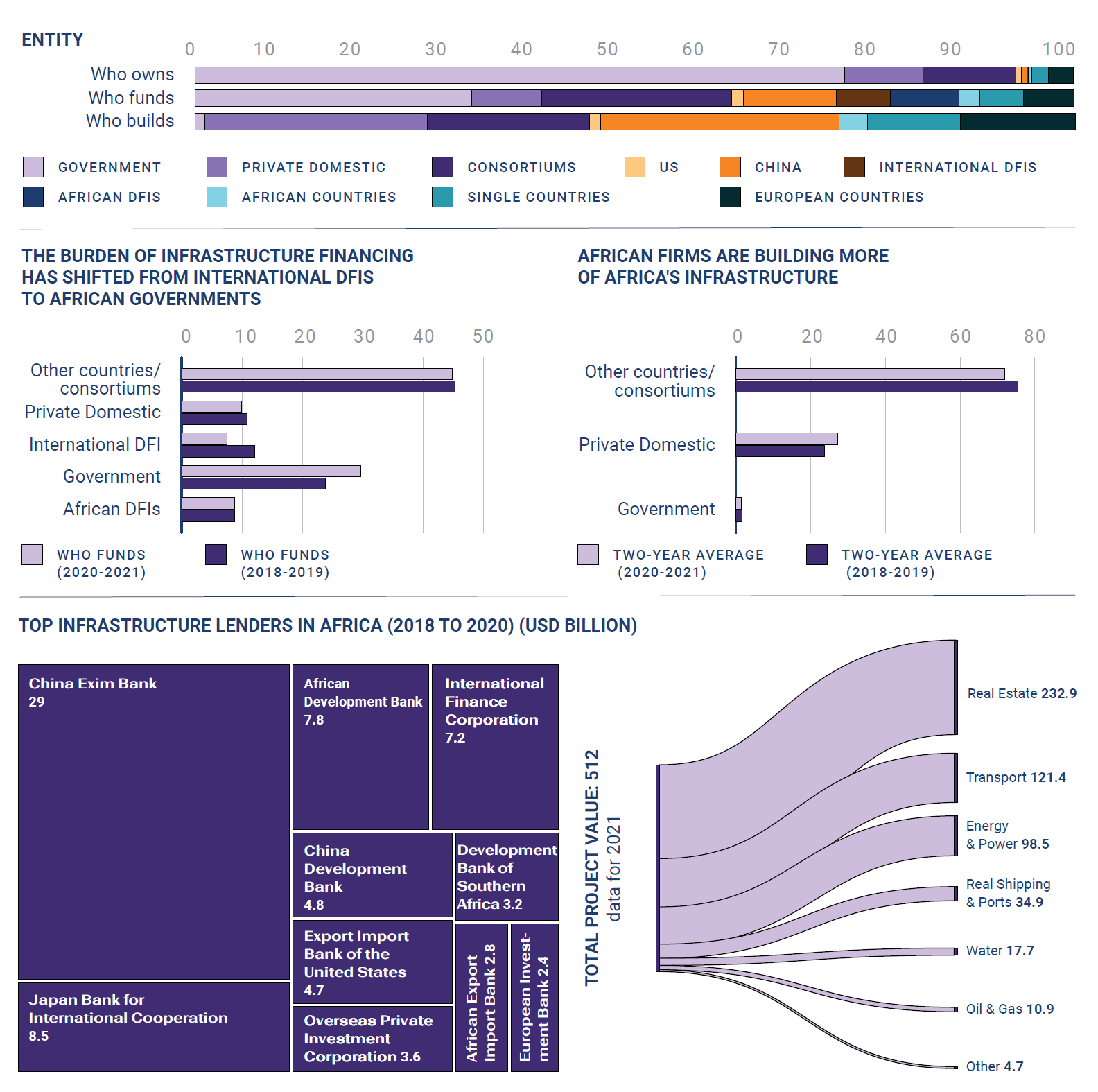

Figure 3: Africa’s infrastructure story

Note: African DFIs are Development Finance Institutions headquartered in Africa (eg the African Development Bank). Consortiums are two or more construction companies or governments holding an equal split of a project’s ownership, building activities, or funding activities. Governments include governments or government departments within the African continent. International DFIs are those headquartered outside Africa (eg the World Bank). Private Domestic firms are African construction firms/financial institutions headquartered in the same African country where it is constructing or funding a project. Single Countries are those that could not be grouped together according to shared geography.

[1] Iddrisu, M, Ohemeng, W and Danquah, M (2022). “Structural transformation in Accra”. ACRC Quantitative Report on Accra, mimeo.

[2] Domfeh, G (2022). “Structural transformation in Accra”. ACRC Qualitative Report on Accra, mimeo.

This blog post is republished with permission from the Brookings Institution. Read the original viewpoint article via the Brookings Institution blog and in Chapter 7 of the Foresight Africa 2023 report.

Header photo credit: Dave Primov / iStock. Women food sellers in Accra, Ghana. Most Ghanaian firms are engaged in the services sector, including wholesale and retail trade.

Note: This article presents the views of the author featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.